A short history of Civilian Defense in the United States during WWII

The 1930s were marked by violent conflicts in China, Ethiopia, and Spain, each revealing a grim new reality in modern warfare: the deliberate and indiscriminate bombing of civilian populations.

In Britain—first subjected to aerial bombardment during World War I by German Zeppelin airships and bomber planes—the threat of future attacks prompted the government to introduce Air Raid Precautions (ARP) in 1935. These measures aimed to mitigate the impact of enemy strikes on both civilian areas and military targets.

With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, Britain rapidly expanded its Civil Defence Services. Thanks to early preparation, the country was able to respond swiftly and effectively to the Luftwaffe’s sustained bombing campaign during the Blitz of London and other cities.

In stark contrast, the United States made minimal progress in civil defense planning during the interwar years. Many Americans believed their geographic isolation would shield them from direct attack, and a strong isolationist movement discouraged involvement in foreign conflicts. As a result, civil defense efforts remained fragmented and largely uncoordinated. It wasn’t until the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 that the U.S. began to take the threat of aerial warfare seriously.

Office of Emergency Management

With Japanese expansion into East Asia and the growing threat of a European conflict, the US embarked upon a limited rearmament programme towards the end of the 1930s. On May 29, 1940, an executive order of the President created the Office of Emergency Management. This office would ultimately cover both the defense of the civilian populace and military/industrial infrastructure.

Three days later, on May 28, the Advisory Commission to the Council of National Defense was reconvened. A subsidiary organization created within the Advisory Commission was the Division of State and Local Cooperation, headed by Frank Bane (also Executive Director of the Council of State Governments). Bane’s Division primarily worked to mitigate the growing problems of the burgeoning rearmament effort. It provided support to states and local councils to manage the growth in industrial output, the growing requirement for manpower, transport infrastructure improvements and the social impact of these changes on local communities.

The Division had made little ground in dealing with civil defense matters before it was abolished. In and out of Congress, people were raising concerns about the government’s poor delivery of civilian defense measures. New York mayor Fiorella La Guardia had received first-hand testimony from firefighters he had sent to London in the early part of the German Blitz on that and other British cities. He wrote that there was a serious need for the US to develop a civil defense program that could adequately deal with a major bombing campaign against US cities.

Though some limited information about blackout requirements and creating air raid shelters was issued by the Division of State and Local Cooperation, little else was looked into. La Guardia and other mayors continued their tirade against Congress for a Federal agency to handle all Civil Defense matters.

New York mayor Fiorella La Guardia and President Roosevelt

Office of Civilian Defense (OCD)

“There is established within the Office for Emergency Management of the Executive Office of the President the Office of Civilian Defense, at the head of which shall be a Director appointed by the President.”

The culmination of the pressure brought to bear by city mayors, combined with the issues caused by the growth of war-related industries, led to the creation of the Office of Civilian Defense (OCD) on May 20, 1941 (replacing the Division of State and Local Cooperation) via Executive Order 8757. New York Mayor La Guardia was the organization’s first unsalaried director, reporting directly to the President.

The OCD’s remit was to coordinate “Federal civilian defense activities which involve relationships between the Federal Government and state and local governments.”:

Assist in the creation of local defense councils to assure effective coordination of Federal relations with State and local governments engaged in furtherance of war programs.

Provide for necessary cooperation with State and local governments with respect to measures for adequate protection of the civilian population and property in war emergencies.

Facilitate participation by all persons in war programs via the recruitment and training of volunteers to provide adequate measures in the event of enemy attack.

The Office of Civilian Defense had four operating divisions:

The Federal State Cooperation Division provided a link between the federal government and local governments to help communities respond to the country's war needs and help the federal government more quickly address individual community needs that might result from a war. It included committees on health, housing, volunteers, recreation, welfare and child care.

The Protection Services Division helped train and organize volunteers in efforts to protect civilians by organizing evacuations, blackouts and auxiliary police and fire services, as well as outfitting protective buildings and managing the demolition of structures damaged by bombings.

The Protective Property Division loaned protective property and equipment purchased by the OCD to local communities. It was responsible for shipping equipment and sending instructions for its care and maintenance.

The Industrial Protection Division helped protect industrial plants against dangers such as fire and enemy sabotage.

The OCD was split into two operating branches:

Civilian Protection Branch (U.S. Citizens Defence Corps) to deal with the protective phases of the mission.

Civilian War Service Branch (U.S. Citizens Service Corps) to deal with the nonprotective phases.

Furthermore, nine Regional Civilian Defense Areas (later called Civilian Defense Regions) were created on July 10, 1941. Each region, headed by a Regional Director, followed the boundaries of the existing Army Corps (later Service Command) Areas.

The function of the Regional Office was to:

Disseminate communications from the Washington Office

Report regulation violations in their jurisdictions to the Washington Office

Coordinate civilian defense measures of the state and local governments and of Federal agencies operating in the region

Coordinate military plans with civilian defense measures.

The nine regions:

Region 1 – Boston, Massachusetts

Region 2 – New York, New York

Region 3 – Baltimore, Maryland

Region 4 – Atlanta, Georgia

Region 5 – Cleveland, Ohio

Region 6 – Chicago, Illinois

Region 7 – Omaha, Nebraska

Region 8 – Dallas, Texas (replaced San Antonio)

Region 9 – San Francisco, California

With the direction of the war, both in the Pacific and in Europe, going the way of the Allies, the OCD's Regional Offices were abolished on July 1, 1944.

State Defense Councils

Each state created defense councils which had varying levels of executive powers. Some states provided their defense councils with wide-ranging powers concerning civil defense matters. In other states the councils were seen as only providing an advisory capacity.

Of utmost importance were the Local Defense Councils (LDC). Manned by necessary public officials (mayors, police and fire commissioners and community leaders, etc). These LDCs were split into two branches akin to the federal OCD; one to protect against enemy action, the other dealing with salvage, housing, health, nutrition, and other community activities. By August 1942, approximately 11,200 local defense councils had been organized.

Metropolitan Civilian Defense Areas

Metropolitan Civilian Defence Areas were established where special administrative arrangements were necessary across multiple counties and even state lines. In every Metropolitan Civilian Defence Area (except New Orleans), the OCD Director appointed a Coordinator of Defense, who was typically subject to the state director's policies and orders. The Coordinator drew advice and assistance from an Advisory Council of Defense, consisting of representatives of the state or states and the local defense councils encompassed in the Metropolitan Area. Such coordinating activities made it possible to enter into mutual agreements for the exchange of personnel, equipment and services, the synchronization and uniform observance of blackouts and air raid drills, and the adoption of integrated evacuation plans covering a wide territory.

By early 1943, 15 Metropolitan Civil Defense Areas had been established: Atlanta, Baltimore, Chicago, Cleveland, Detroit, Houston, Los Angeles, New Orleans, Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Portland, San Francisco Bay, Seattle, Toledo, and Washington.

La Guardia and Eleanor Roosevelt

La Guardia showed little interest in organizing volunteers within the social welfare programs that formed part of the OCD's mission; his focus was the protective measures. This weakness led to the Budget Bureau threatening to withhold funds from the OCD unless it undertook both of its mission requirements.

To ensure compliance, La Guardia appointed Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt as Assistant Director in Charge of Voluntary Participation in September 1941. The First Lady saw the OCD as a way to encourage citizen participation in the war effort, and strengthen American democracy. She believed that “we must continue with the progressive social legislation as part of national defense.”

Drawing on the example of Lady Stella Reading, who ran Britain’s Women's Voluntary Services for Civil Defence, the President’s wife encouraged American women to become involved in the war effort. To this end, working with Florence Kerr, the head of Works Progress Administration Community Service Projects, a plan entitled American Social Defense Organization was created.

After joining the OCD, Eleanor Roosevelt quickly set about organizing the national office and built a strong team of assistants and advisors. She worked across various agencies to drive through federal funds for day care, maternal support, children’s health, and child-welfare services. However, some poor decisions regarding hiring friends to run some OCD departments led to criticism and ridicule. This was especially the case with dancer Mayris Chaney, who received a substantial salary to work as an assistant in the OCD physical fitness program.

Eleanor Roosevelt, La Guardia and James Landis

James Landis takes over

“The greatest trouble with civilian defense is that people have not awakened to the fact that the United States is at war. ”

With America's entry into the war following Pearl Harbor, the President decided to put the civil defense program under full-time leadership. In January 1942, the President named James Landis, as a full-time special executive assistant.

With the resignations of La Guardia and Mrs. Roosevelt in February 1942, Landis was elevated to Director of the OCD (this was made official in April of 1942).

Landis made immediate changes to the OCD. New faces were brought in and some agencies were removed or handed off to other government departments. Whilst the dual mission remained (protective and non-protective), he withdrew the OCD’s requirement "to sustain national morale." Further, a single "Civilian Defense Board replaced the Board of Civilian Protection and the Volunteer Participation Committee.

Under Landis, the Citizens Defense Corps of approximately 10 million volunteers provided a wide range of protective services. Over 8.5 million of these volunteers had specific assignments under the protective services programs.

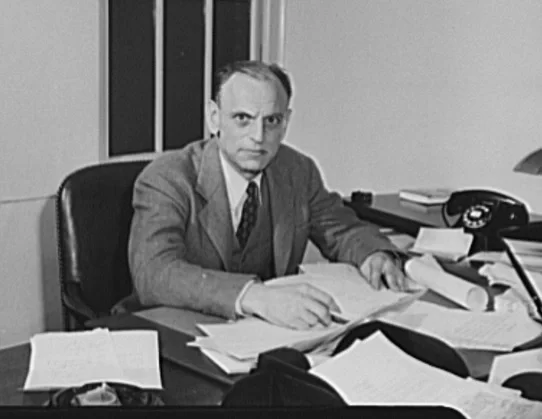

James Landis, Director of the Office of Civilian Defence

Additionally, the President's order of May 19, 1942, directed OCD to include facility a security program:

Serve as the center for the coordination of plans in this field sponsored or operated by the several Federal departments and agencies;

Establish standards of security to govern the development of security measures for the nation's essential facilities;

Review current and future plans and require the adoption of necessary additional measures; and

Take steps to secure the cooperation of owners and operators of essential facilities, and of State and local governments, in carrying out adequate security measures.

Separate Presidential orders issued earlier gave the military departments and the Federal Power Commission specific responsibility for protecting vital war facilities.

Under this program, Federal participating agencies dealt directly with the facilities or with State or local authorities controlling action therein. Coordination was maintained at the Federal, State and local levels. Liaison was also maintained with the military departments, the Federal Power Commission, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Within OCD, a Facility Security Division administered the program with the help of OCD regional, State and district facility security officers.

Landis also expressed the desire to run his own information office instead of being part of a centralized information service in the Office of Emergency Management. Because information was so basic to the OCD mission, Landis believed that the promotion of OCD programs should be handled within his own organization. After some negotiation with the Budget Bureau, OCD set up its own information office.

Landis directed the OCD until August 1943. By then, the possibility of an air attack on the U.S. had long since passed, leaving little prospect of seeing the civilian protection forces being tested. Landis felt, too, that the State and local units were by then sufficiently developed to enable them to discharge their responsibilities with minimum guidance from Washington. He recommended, therefore, the abolition of OCD, and the transfer of the protective services to the War Department and the mobilization services to the Federal Security Agency.

This proposal met with resistance from the President and the War Department, despite the fact that it had assisted significantly in organizing the protective services. The reasons for this opposition are not entirely clear, although the realization that the danger of enemy attack had passed and that there was still a war to fight entered the picture.

Directors John Martin & William N. Haskell

The Director of the Budget also objected to the Landis proposal, and President Roosevelt decided to keep the agency going. John Martin served as acting director of the OCD for the next six months. Martin’s tenure saw a decline in the organization’s morale as uncertainty about his position, and whether the agency would continue, impacted across the entire organisation.

In the meantime, upon advice from the War Department to the OCD, the protective services in the States and localities were placed on a stand-by basis (as the risk of attack diminished). Martin left in March 1944, and the post of director went to retired Lt. General William N. Haskell. Over the ensuing sixteen months the OCD cut back its operations. The new President, Harry Truman, on 4 June, 1945 signed Executive Order 9562 to terminate the OCD, and the organization officially shut down on 30 June, 1945.

OCD's protective property and records were assigned to the Department of Commerce, and the Treasury Department was directed to "wind up the affairs of the Office." State and local organizations disbanded soon thereafter.

All of the OCD's programs came to an end, with the exception of the Civil Air Patrol, which had been transferred to the War Department a few years before. However, civil defense was not entirely finished. In 1950, President Truman established the Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA) to oversee States' civil defense efforts, such as building shelters to protect against the growing nuclear threat. The Office of Civil and Defense Mobilization (created in 1958) was replaced by the Office of Civil Defense (OCD) between 1961 and 1964. The organization was renamed the Defense Civil Preparedness Agency on 5 May, 1972, and was abolished on 20 July, 1979, pursuant to Executive Order 12148. Its duties were given to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

Directors U.S. Office of Civilian Defense – 1941 to 1945

Fiorello LaGuardia – May 20, 1941 to February 11, 1942

James Landis – February 12, 1942 to September 8, 1943

John Martin (Acting) – September 9, 1943 to March 9, 1944

(Lt. Gen.) William N. Haskell – March 10, 1944 to June 30, 1945

Was the Office of Civilian Defense a success?

Overall, between 1941 and 1945 the running the OCD was marked by considerable conflict and confusion. There was often conflict between the agency’s programs, which bypassed individual State practices.

Virtually all reviews of the OCD draw the same conclusion: that the agency's image and record left much to be desired. As the war progressed and the absence of an enemy attack, even the protective aspects of the program began to draw criticism in Congress and the press.

Testifying later before the War Department Civil Defense Board, former OCD Director Landis observed: "There's a limit to the business of being an air raid warden, especially when no bombs are dropping."

A post-war War Department's Provost Marshal General report discussed the problems of OCD's performance:

A lack of advance planning

An absence of unified command and authority

The assignment to the agency of responsibilities extraneous to civil defense

A second study by a War Department Civil Defense Board summed up the strengths and weaknesses of the OCD thus:

The OCD mobilized a vast volunteer organization but it was never tested even by a minor enemy attack.

Low level civil defense planning was generally good.

Regional control was weak due to lack of authority.

No clear delineation of civil defense responsibilities existed.

The social activities of the agency diverted effort from the primary mission of civil defense.

No advanced planning was evident.

Little experienced leadership.

Adherence to the principle of States' rights and traditional municipal individuality-blocked standardization of plans in certain instances.

Due to the lack of authority in the Office of Civilian Defense, State and local leaders frequently looked to the Army for command decisions.

In summation the Board felt that the wartime OCD would have been unable to have dealt with a heavy enemy attack and that the US military would have been required to have taken over.